Unit 2 homework 1 inductive reasoning – Unit 2 Homework 1: Inductive Reasoning embarks on a captivating journey into the realm of logical reasoning, unveiling the intricacies of inductive reasoning and its profound applications across diverse fields. This comprehensive guide delves into the depths of this fundamental concept, exploring its methods, strengths, weaknesses, and potential pitfalls, empowering readers with a comprehensive understanding of its significance in problem-solving and knowledge acquisition.

Inductive reasoning, a cornerstone of human cognition, plays a pivotal role in drawing inferences and making predictions based on observed patterns and specific instances. By examining real-world examples, this guide illuminates the practical applications of inductive reasoning, showcasing its versatility in various disciplines, from scientific research to everyday decision-making.

1. Introduction: Unit 2 Homework 1 Inductive Reasoning

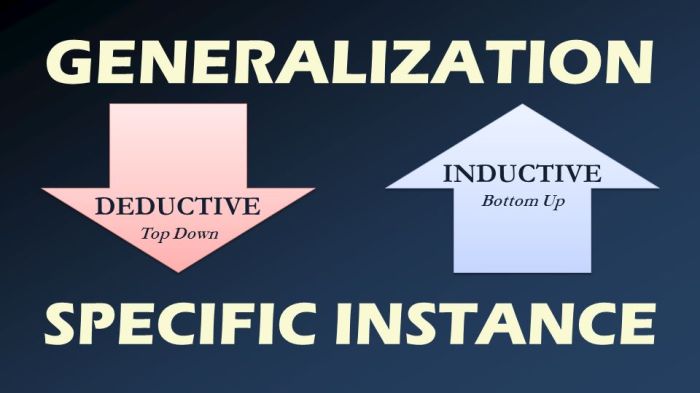

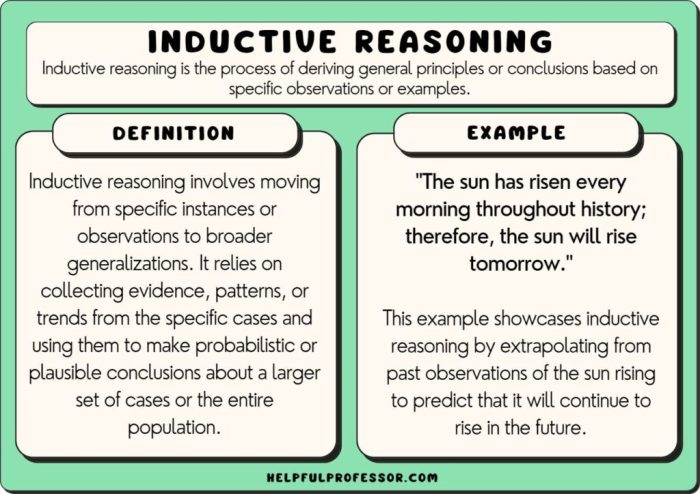

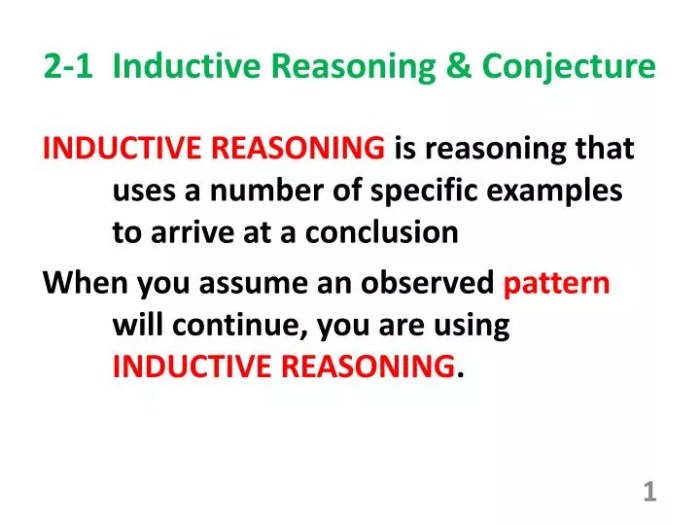

Inductive reasoning is a type of logical reasoning that draws general conclusions from specific observations or premises. It involves making inferences about the future or the unknown based on past experiences or patterns. The purpose of inductive reasoning is to make predictions or generalizations that can be used to make decisions or understand the world around us.

2. Examples of Inductive Reasoning

Here are some real-world examples of inductive reasoning:

- Observing that all swans you have ever seen are white, and concluding that all swans are white.

- Noticing that the sun has risen every day in your lifetime, and inferring that the sun will rise tomorrow.

- Examining a sample of products from a production line and concluding that the entire batch is of good quality.

3. Methods of Inductive Reasoning

There are several different methods of inductive reasoning, including:

- Generalization:Drawing a general conclusion from a number of specific observations.

- Analogy:Comparing two similar situations and inferring that they will have similar outcomes.

- Causal reasoning:Inferring that one event caused another based on their temporal and logical relationship.

Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of method depends on the specific situation and the available evidence.

4. Applications of Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is used in a wide range of fields, including:

- Science:Scientists use inductive reasoning to develop hypotheses and theories based on experimental data.

- Medicine:Doctors use inductive reasoning to diagnose diseases and prescribe treatments based on patient symptoms and medical history.

- Business:Marketers use inductive reasoning to identify consumer trends and develop marketing campaigns.

- Law:Lawyers use inductive reasoning to build cases and draw conclusions based on evidence.

5. Fallacies of Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning can be prone to fallacies, which are errors in reasoning that lead to invalid conclusions. Some common fallacies of inductive reasoning include:

- Hasty generalization:Drawing a general conclusion from a small or unrepresentative sample.

- False analogy:Comparing two situations that are not truly similar.

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc:Assuming that because one event follows another, the first event caused the second.

It is important to be aware of these fallacies and to use inductive reasoning carefully to avoid making incorrect conclusions.

Popular Questions

What is the primary purpose of inductive reasoning?

Inductive reasoning aims to draw general conclusions or make predictions based on specific observations or patterns, allowing us to make inferences about the world around us.

Can inductive reasoning guarantee absolute certainty?

No, inductive reasoning does not provide absolute certainty but rather offers probabilistic conclusions. The strength of the conclusion depends on the representativeness and sufficiency of the evidence.

What are some common fallacies associated with inductive reasoning?

Inductive reasoning can be susceptible to fallacies such as hasty generalization, where conclusions are drawn from insufficient evidence, or confirmation bias, where individuals selectively seek information that confirms their existing beliefs.